October 2, 2018

Background

Background

Surveys are ubiquitous in the social sciences, and the best of them are meticulously planned out. Statisticians often decide on a sample size based on a theoretical design, and then proceed to inflate this number to account for “sample losses”. This ensures that the desired sample size is achieved, even in the presence of non-response. Factors that reduce the pool of interviews include participant refusals, inability to contact respondents, deaths, and frame inaccuracies.1 The more non-response, the more a study becomes open to criticism about its veracity.

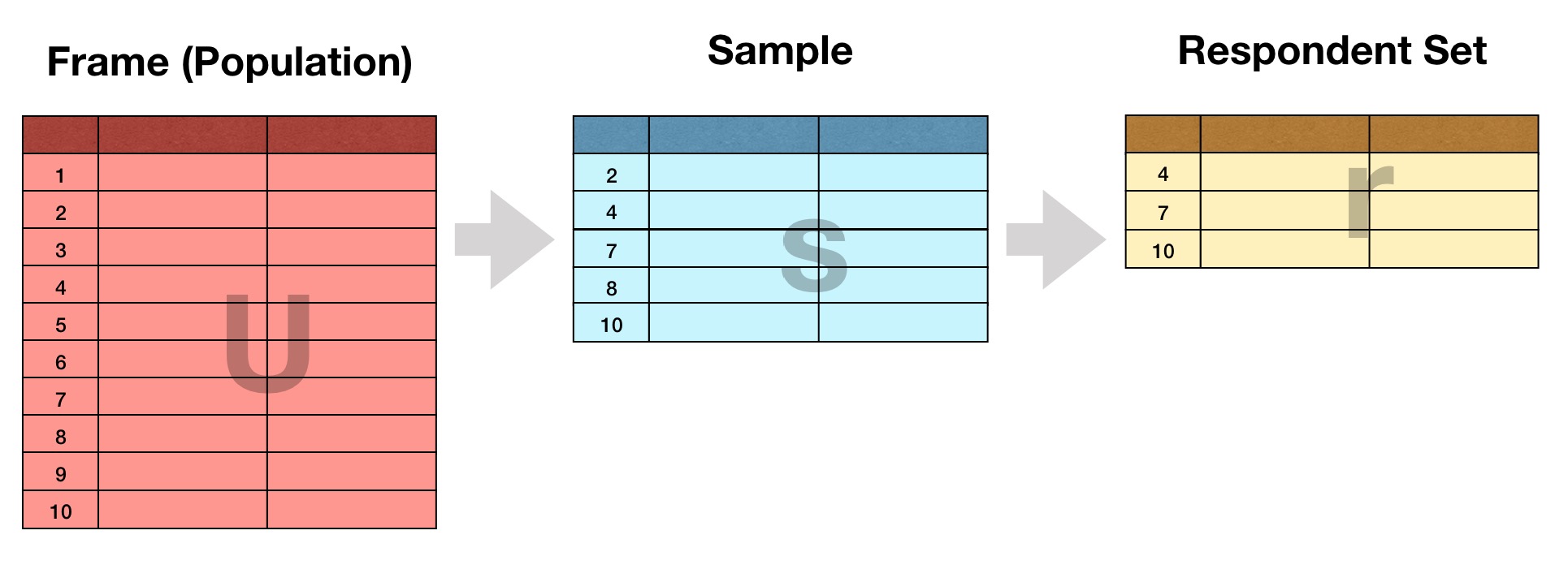

To simplify communication about non-response, a set of “outcome rates” have emerged over time. These rates are essentially quality declarations about the operational elements in a survey. Broadly speaking, they relate how well an actual respondent set r matches its intended sample s.

Some of popular outcome rates include:

- Response Rate: The proportion of your sample that results in an interview.

- Cooperation Rate: The proportion of people contacted who participate in your survey.

- Refusal Rate: The proportion of your sample that refused to participate.

- Contact Rate: The proportion of sampled cases where you manage to reach the respondent.

- Location Rate: The proportion of cases (say, in an establishment survey) that you manage to locate.

Sounds straightforward. But for a long time, it was common to find disparate definitions of these rates. This made it hard to judge the quality of one survey against another.

What Problem Does the Package Solve?

What Problem Does the Package Solve?

The package calculates standard outcome rates in R in order to encourage transparent research, open methods, and scientific comparability. It does so using the American Association of Public Opinion Research’s (AAPOR) definitions of the rates, which are the industry standard. By collecting them in one package, it saves you the time of repetitively looking up each rate and calculating them separately.

As a contrived example, let’s assume we draw a sample of 10 people. Five individuals provide a complete interview (I), one provides a partial interview (P), one refuses to participate (R), and two are unreachable but known to be eligible (NC). Our 10th case is also unreachable but we don’t know if they are illegible to begin with (UH).

library(outcomerate)

x <- c(I = 5, P = 1, R = 1, NC = 2, UH = 1)

outcomerate(x)

#> RR1 RR2 RR5 RR6 COOP1 COOP2 COOP3 COOP4 REF1 REF3 CON1 CON3 LOC1

#> 0.50 0.60 0.56 0.67 0.71 0.86 0.71 0.86 0.10 0.11 0.70 0.78 0.90

By default, the function returns only the rates that are defined based on the input. Here, we see that the example case achieved a Response Rate 2 (RR2) of 60%, and a Cooperation Rate 1 (COOP1) of 71%. Other rates, such as Response Rate 3 (RR3), are not returned as they only become available if you specify additional parameters (see ?outcomerate for details).

The same output can be obtained by specifying the input as a vector of cases. This format may be more natural if you have a dataframe of interviews, or a stream of daily data coming from a server:

y <- c("I", "I", "I", "I", "I", "P", "R", "NC", "NC", "UH")

outcomerate(y)

#> RR1 RR2 RR5 RR6 COOP1 COOP2 COOP3 COOP4 REF1 REF3 CON1 CON3 LOC1

#> 0.50 0.60 0.56 0.67 0.71 0.86 0.71 0.86 0.10 0.11 0.70 0.78 0.90

outcomerate() replicates some of the functionality that AAPOR already makes available in their Excel-based calculator. Theirs is a wonderful free tool, but has some limitations. For one, the Excel calculator is not designed to compute many rates by sub-domain. In my own work, I often need rates in real time by day, by researcher/enumerator, and by geography. Doing each analysis in a separate Excel workbook is impractical. Instead, outcomerate() makes it easy to achieve this with dplyr, aggregate(), or data.table.

Another problem is that Excel is notorious for failing silently. It will give you a result even if the input contains errors or inconsistencies. Especially when I am updating this information daily, those mistakes are quick to slip in. outcomerate helps overcome this by failing fast and failing helpfully:

outcomerate(c("I", "I", "P", NA))

#> Error in assert_disposition(x): The input 'x' contains NA values. Consider converting them to

#> NE (known inelligibles) or UO / UH (unknown elligibility)

The package also implements weighted calculations of rates. Weighted figures further advance reproducible research because they typically estimate the outcome rate at the population level rather than for the sample. This is useful information to share with the world, as it helps others plan for sample losses in future studies. Unless you plan to replicate the sampling design exactly, it is often more useful to know the (weighted) population rate and/or rates by sub-domain.

outcomerate(y, weight = 10:1) # fake weights

#> RR1w RR2w RR5w RR6w COOP1w COOP2w COOP3w COOP4w REF1w REF3w

#> 0.73 0.82 0.74 0.83 0.82 0.92 0.82 0.92 0.07 0.07

#> CON1w CON3w LOC1w

#> 0.89 0.91 0.98

Future Development

Future Development

I welcome contributions to outcomerate (#hacktoberfest). Some ideas for enhancements include:

- Implementing other sections from the AAPOR manual (#2): Though arguably less popular than the “main” outcome rates, AAPOR has separate chapters for telephone surveys, online panels, and mixed-mode survey work. I chose not implement these initially, because some of the definitions differ despite using similar codes.

- Publication-ready tables (#3): I imagine that many users will want to make publication-ready tables of the outcome rates. It would be nice to have a function that returns professional tables in LaTex and HTML.

- Adding methods to calculate standard error (#4): I am also considering functions that provide the standard error of the rates.

- Writing new vignettes: Some topics I wish to write more about include real-time monitoring of survey quality (#5), and variance calculations of outcome rates in complex designs (#6).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

My thanks goes to Neil Richardson, Carl Ganz, and Karthik Ram for their peer review and editorial support at rOpenSci. outcomerate is better for it, and my programming style and knowledge has improved. Naturally, I also wish to acknowledge AAPOR for advancing the practice of survey research— this package is built on the definitions they helped standardize.

-

Frame inaccuracies are mistakes in the list of population elements from which the sample is drawn. Their post-facto discovery has implications for design-based inference, because the original sample then no longer relates cleanly to the target population. Such inaccuracies impact outcome rate calculation, depending on whether or not you use your initial mistaken frame or make an adjustment to correct for ineligible cases. ↩︎